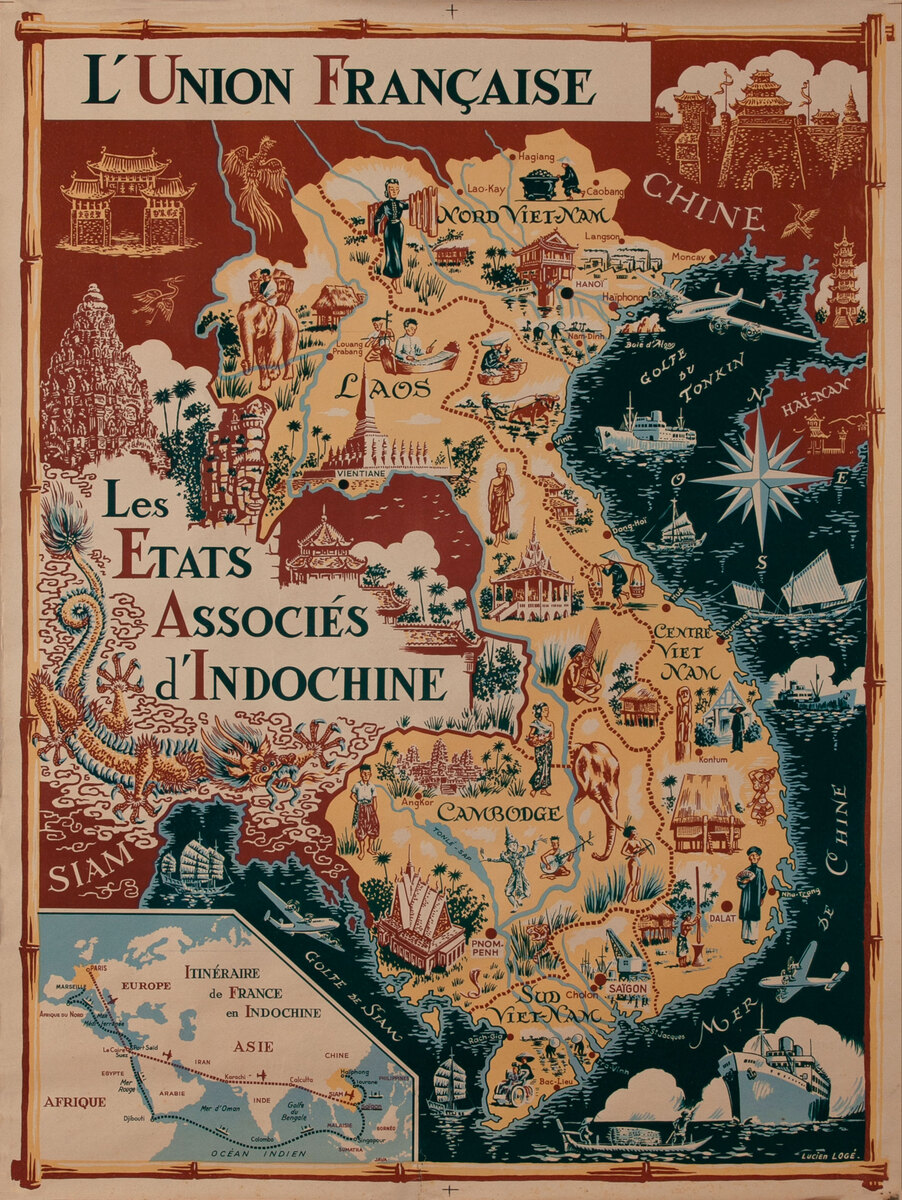

L'Union Française - Les Etats Associes d'Indochine

- 1953

- Lucien Loge

-

23 1/2 x 31 1/2 inches ~ (58 x 78 cm)$2,640

- Linen backed

Linen backing is the industry standard of conservation. Canvas is stretchered and a sheet of acid free barrier paper is laid down. The poster is then pasted to the acid free paper using an acid free paste. This process is fully reversible and gives support to the poster. A border of linen is left around the poster and can be used by a framer to mount the poster so that nothing touches the poster itself.

The price of this poster includes linen backing.

- Add to Cart Add to Wishlist E-Mail Us About This Poster

Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia

Lucien Loge’s map depicts the proposed French Union’s Associated States of Indochina, the failed effort to prolong France’s colonial empire as a voluntary commonwealth. In this map, Vietnamese political agency is silenced. There is no depiction of the Viet Minh’s increasingly successful guerilla campaign, nor of any nationalist or Marxist activity. Rather, Vietnamese, Khmer, Lao, and ethnic highlanders engage in peaceful and industrious behavior such as growing rice and other rural labor. Musicians, a dancer, a monk, and a Confucian scholar show the region’s idealized cultural traditions. The only interaction with modernity is a coal miner in the far north and a rickshaw puller in the south. France’s modernization can be seen in the industrial activity near Hanoi and Saigon, and the planes and steamships which offer to connect this timeless land with France and the world beyond. In one concession to the changed political reality, Loge uses the once-banned name Vietnam, instead of the French-imposed division of the nation into Cochinchine, Annam, and Tonkin. However, the map does perpetuate these boundaries by separating Vietnam into South, Central, and North along the old imperial framework.